![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() EDUCATION EXHIBIT

EDUCATION EXHIBIT

Balloon Dilation and

Stent Placement for

Esophageal Lesions:

Indications, Methods,

and Results

Eric Therasse, MD Vincent L. Oliva, MD Edwin Lafontaine, MD

ONLINE-ONLY

Pierre Perreault, MD Marie-France Giroux, MD Gilles Soulez, MD

CME

See www.rsna

.org/education

/rg_cme.html.

LEARNING

OBJECTIVES

After reading this

article and taking

the test, the reader

will be able to:

Discuss the indica-

tions for and results

of esophageal stent

placement.

Describe the inser-

tion techniques, ad-

vantages, and limita-

tions associated with

commercially avail-

able stents.

Recognize and

manage complica-

tions that may occur

following esophageal

stent placement.

Esophageal balloon dilation and expandable stent placement are safe,

minimally invasive, effective treatments for esophageal strictures and

fistulas. These procedures have brought the management of dysphagia

due to esophageal strictures into the field of interventional radiology.

Esophageal dilation is usually indicated for benign stenoses and is

technically successful in more than 90% of cases. Most patients with

esophageal carcinoma are not candidates for resection; thus, the main

focus of treatment is palliation of malignant dysphagia and esophagores-

piratory fistulas. Esophageal stent placement, which is approved only

for malignant strictures, is one of the main therapeutic options in af-

fected patients and relieves dysphagia in approximately 90% of cases.

Dedicated commercially available devices continue to evolve, each with

its own advantages and limitations. Stent placement is subject to tech-

nical pitfalls, and adverse events occur following esophageal proce-

dures in a minority of cases. Although chest pain is common and self-

limited, reflux esophagitis, stent migration, tracheal compression, and

esophageal perforation and obstruction require specific interventions.

In many cases, these complications can be recognized and treated by

the interventional radiologist with minimally invasive techniques.

RSNA, 2003

Abbreviation: FDA Food and Drug Administration

Index terms: Esophagus, diseases, 71.291, 71.321, 71.33 Esophagus, grafts and prostheses, 71.1269 Esophagus, interventional procedures,

Esophagus, neoplasms, 71.30 Esophagus, stenosis or obstruction, 71.74 Stents and prostheses, 71.1269

RadioGraphics 2003; Published online 10.1148/rg.231025051

From the Departments of Radiology (E.T., V.L.O., P.P., M.F.G., G.S.) and Surgery (E.L.), Centre Hospitalier de l’Universite´ de Montre´al

(CHUM), 3840 St Urbain St, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2W 1T8. Recipient of a Certificate of Merit award for an education exhibit at the 2001

RSNA scientific assembly. Received March 8, 2002; revision requested April 25 and received May 24; accepted May 28. Address correspondence

to E.T. (e-mail: [email protected]

RSNA, 2003

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() January-February 2003

January-February 2003

Introduction

Most cases of malignant dysphagia are due to

esophageal carcinomas that are unresectable at

presentation and for which palliation will be the

focus of treatment (1). Dysphagia has long been

treated with surgical and endoscopic interven-

tions. Esophageal bougienage may be performed

without guidance, and a rigid plastic stent could

be inserted endoscopically with or without fluoro-

scopic guidance. However, crossing tight esopha-

geal stenoses and positioning metallic stents are

sometimes difficult or impossible without fluoro-

scopic guidance and appropriate catheter technol-

ogy. Radiologists, who are already accustomed to

using similar materials and techniques for vascu-

lar and nonvascular interventions, are in the ideal

position to perform these interventions safely and

relatively easily. Esophageal procedures should be

adequately tailored to the underlying disease, and

one should take advantage of the characteristics

of various devices in specific situations. Although

many benign strictures can be treated with bal-

loon dilation, esophageal stent placement will be

one of the main palliative options in malignant

dysphagia. In addition, the radiologist should be

aware of possible complications of esophageal

interventions because in many cases he or she will

be able to prevent or treat these complications.

In this article, we review the indications for

and the methods and outcomes of balloon dila-

tion and stent placement for esophageal stric-

tures. We also describe various commercially

available stents as well as the advantages and limi-

tations of each stent. In addition, we discuss spe-

cific situations that require careful attention and

the management of possible complications of

stent insertion.

Indications

Esophageal dilation is usually indicated for be-

nign stenoses such as rings, webs, achalasia, and

strictures caused by peptic, postsurgical, postscle-

rotherapeutic, or corrosive injury (2). Dilation of

extrinsic esophageal compression is usually inef-

fective. In malignant lesions, dilation is some-

times performed prior to stent insertion or can be

used as a temporizing measure prior to surgery or

radiation therapy, but it is generally ineffective if

used alone.

RG f Volume 23 ● Number 1

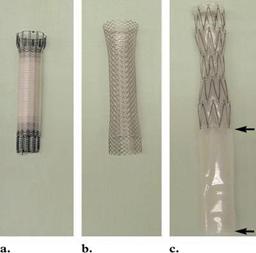

Figure 1. Photographs show FDA-approved

covered esophageal stents: the Ultraflex stent (a),

the Wallstent II (b), and the Z-stent without an-

chors (shown with an antireflux valve [arrows])

(c)

Esophageal stents have been approved by the

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only

for malignant strictures, whether intrinsic (esoph-

ageal carcinoma) or extrinsic (eg, lung carci-

noma). The use of stents in benign lesions is

plagued by a high long-term complication rate

and leads to tissue hyperplasia with recurrent

esophageal stenosis (3). However, good results

have been reported in benign lesions with retriev-

able stents that are left in the esophagus for a few

months (4). Covered metallic stent placement is

now the primary treatment for malignant bron-

choesophageal fistulas and is also accepted as the

main treatment option for malignant dysphagia in

patients with poor functional status who cannot

tolerate radiation therapy or chemotherapy, who

have advanced metastatic disease, or in whom

previous therapy has failed (5).

FDA-approved Stents

There are currently three self-expandable esopha-

geal stents approved by the FDA (Fig 1), and

their characteristics are listed in Table 1 (1). All

currently available esophageal stents are covered

to prevent tumor ingrowth and allow treatment of

fistulas, whereas their extremities are uncoated to

permit anchoring and prevent migration. These

stents have now completely replaced rigid plastic

tubes, which were associated with a high proce-

dural complication rate and poor palliation (5).

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() RG f Volume 23 ● Number 1

RG f Volume 23 ● Number 1

Therasse et al 91

Figure 2. Drawings illustrate the delivery system of the Ultraflex stent. (a) The distal release system allows elimi-

nation of proximal foreshortening during deployment and is best suited for stent placement in the middle and upper

esophagus. (b) The proximal release system allows elimination of distal foreshortening during deployment and is best

suited for stent placement in the gastroesophageal junction. Arrows indicate how to release the stent by pulling out

the string. (Courtesy of Microvasive/Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass.)

Table 1

Characteristics of Covered Metallic Esophageal Stents

Feature

Deployment

Size of delivery system

Material

Design

Radial force

Edges

Lumen diameter (mm)

Length (cm)

Shortening (% of length)

Ultraflex*

String release

24-F

Nitinol

Knitted

Low

Uncoated, smooth

Wallstent II*

Sheath, pusher rod

18-F

Stainless steel

Mesh

High

Uncoated, sharp

Z-stent

Sheath, pusher rod

24–31-F

Stainless steel

Zigzag

Moderate

Coated, smooth

*Microvasive/Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass.

Wilson-Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC.

Ultraflex Stent

The Ultraflex stent is mounted on a delivery cath-

eter, unprotected by a sheath, and restrained by a

string that must be pulled out to release the stent.

Because of the stent shortening that occurs during

deployment, two delivery systems are proposed

(Fig 2). Preinsertion dilation is often required

because the unprotected surface of the stent and

the large profile of the delivery system produce

friction during advancement through tight esoph-

ageal strictures. Lubrication of the Ultraflex stent

delivery system is recommended to help with in-

sertion. Stent shortening, the poor radiopacity of

nitinol, and the need to predilate tight strictures

make Ultraflex stent deployment more difficult

than deployment of the Wallstent. The lower ra-

dial force and greater flexibility of the Ultraflex

stent are probably responsible for less postdeploy-

ment chest pain and better patient tolerance;

however, the Ultraflex stent also requires more

time to fully expand in comparison with other

stents (6). Smooth, nontraumatic edges should

offer protection against esophageal erosions and

bleeding. The Ultraflex stent is also available in a

22–23-mm-diameter version for use in dilated

esophagus.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() January-February 2003

January-February 2003

Figure 3. Photographs illustrate the de-

livery system of the Wallstent. (a) Wall-

stent before deployment. (b, c) To deploy

the stent, the inner catheter (arrow in b) is

held stationary while the outer sheath (ar-

rowhead in b) is withdrawn, allowing distal

to proximal stent release (c).

Wallstent

The Wallstent is mounted on a delivery catheter

and covered by a sheath. Stent deployment is il-

lustrated in Figure 3. Stent shortening occurs at

both extremities and must be considered when

choosing the appropriate stent length. The Wall-

stent is easy to deploy and is loaded in a small

RG f Volume 23 Number 1

(18-F) sheath that allows crossing of most lesions

without preinsertion dilation. The radiopacity of

the stent is excellent, and deployment requires

minimal traction on the sheath. The uncoated

sharp filaments of the stent extremities can be

traumatic but should reduce the occurrence of

migration. The Wallstent has the highest radial

force (more appropriate for extrinsic compres-

sion) of the FDA-approved stents and is more

likely to produce postdeployment chest pain.

Z-stent

The Z-stent must be inserted into the delivery

system before use (Fig 4). The Z-stent has good

radiopacity, and its shortening is minimal. How-

ever, considerable traction must be applied on the

outer tube to release the stent from the bulky

31-F sheath, which often requires preinsertion

dilation to 12 mm. In addition, removal of the

delivery system is often difficult because its tip has

a tendency to catch the stent. The Z-stent has

minimal flexibility, making it less appropriate for

tortuous anatomic structures. The stent is avail-

able with uncoated flange ends without anchors

(31-F) and with coated flange ends with anchors

(24-F). The former version is also available with

an antireflux valve to be used when the stent has

to cross the gastroesophageal junction. This

windsock-type valve, an extension of the stent

polyurethane membrane 8 cm beyond the lower

metal cage, is designed to invert inside the stent

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() RG f Volume 23 ● Number 1

RG f Volume 23 ● Number 1

Therasse et al 93

Figure 4. Photographs illustrate the delivery system of the Z-stent. (a) The stent is lubricated and is loaded

through a funnel in the tip of the outer tube by pulling on threads (arrow). (b) The guiding tip (arrowhead) is

adapted to the sheath by pulling on the other end of its shaft (arrow). (c) To deploy the stent, the locking device is

pulled out and the inner catheter (arrow) is held stationary while the outer sheath (arrowhead) is withdrawn. The

thread is cut and removed before retrieving the delivery system.

when gastric pressure rises above a threshold,

thereby allowing patients to belch or vomit (7).

The Z-stent has a higher migration rate when

placed across the gastroesophageal junction (6).

Table 2 summarizes the strengths and weak-

nesses of the various FDA-approved esophageal

stents.

![]()

|