ESTHETICS IN ADULT ORTHODONTICS - Paul Yurfest, DDSIn honor and

memory of Dr. Marvin C. Goldstein, mentor and teacher.

INTRODUCTION

It is the rare patient who understands that ideal orthodontic form and function

are the foundation of esthetic treatment. When orthodontic remedies are

prescribed as a first line of treatment but rejected by the patient, then all

subsequent esthetic procedures become compromise treatments. This is not

necessarily a negative; it is just a fact.

The quest to practice optimal esthetic dentistry requires an understanding of

certain fundamental aspects of orthodontics and orthodontic therapies. This

chapter does not address the radiographic analysis (cephalometrics) necessary

to make a thorough evaluation in orthodontic complexities. However, it is

imperative to master these analyses before undertaking a complex orthodontic

plan. This discussion will focus on the treatment of limited problems requiring

less complex types of orthodontic appliances and limited tooth movement to

achieve a specific esthetic result. More difficult esthetic problems that are

treated with complex orthodontic therapies will also be shown to demonstrate

the scope of available treatments.

When a patient is asked what an orthodontist does, the likely response is usually

something about "straightening teeth" or "fixing a smile."

The typical patient's idea of orthodontic treatment remains based on the

concept that he or she would have to wear "metal braces," that these

braces are uncomfortable, and that they are unattractive. Therefore, if we are

to motivate our patients to consider orthodontic treatment, we must also

demonstrate the range of alternative esthetic orthodontic treatment options.

The practice of esthetic dentistry requires an understanding of the techniques that

are now available for orthodontic therapies that can assist the dentist in

pursuing an acceptable esthetic result.

When dental and dentofacial esthetics are concerned, orthodontic therapy should

be an integral consideration in any treatment plan. Modifying tooth position in

anterior teeth prior to the fabrication of esthetic restorations such as

porcelain laminate veneers, composite resin bonding, or crowns may greatly

enhance the final esthetic and functional result. Factors such as restoration

width and length are greatly affected when crowding, spacing, protrusion, or

retrusion is present prior to initiating prosthetic restorative procedures.

Sometimes, orthodontic treatment alone can be the definitive treatment of

choice to satisfy the patient's esthetic issues. There is, of course,

reluctance by many patients to undergo orthodontic treatment. Advances 14314x2314o in the

comfort, esthetics, and efficiency of orthodontic treatment and appliances

(clear braces, lingual braces, Invisalign [Align Technology,

PREVENTIVE TREATMENT

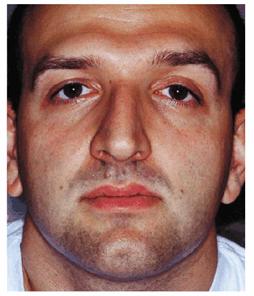

The concept of prevention in general health care has had a slow acceptance rate

when compared specifically to the dental component. Dental professionals and

patients alike have historically embraced preventive dental care. However,

disregarding orthodontic preventive diagnostics is a disservice to patients

that should be addressed. Too many adults who have had lifelong preventive

dental care are suddenly diagnosed with a significant dental malocclusion.

Severe overbite, where the upper front teeth cover the lower front teeth when

the patient occludes, is a problem that the primary caregiver (dentist or

dental hygienist) should easily recognize. Patients should be informed of the

long-term destruction that such a condition can cause. The developing dentition

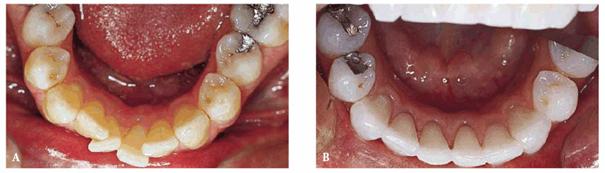

(Figures 25-1A, and 25-1B) requires attention from an

orthodontic perspective prior to eruption of all of the permanent teeth. Severe

crowding, midline shift, and developing crossbite are problems that will likely

become worse and eventually cause needless wear to the anterior teeth if left

untreated. Patients with these conditions should be diagnosed by the general

dentist and, when appropriate, referred to an orthodontist.

Figure 25-1A: Front view of a mixed dentition patient age 11. Notice the midlines that do not coincide, anterior open bite, and crossbite tendency of the upper premolars indicating a constricted maxillary arch.

Figure 25-1B: Side view shows a large canine "bulge" that indicates significant trouble in the eruption process of the maxillary canines.

ORTHODONTIC TOOTH MOVEMENT

When a tooth is repositioned, the entire tooth attachment, including bone and

gingiva, migrates with it. This is particularly important where there is uneven

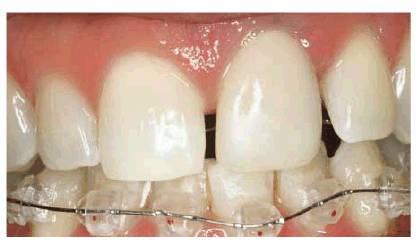

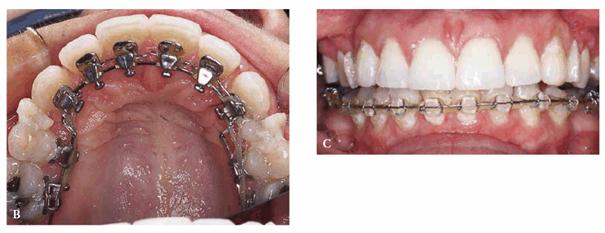

gingival height at the maxillary central incisors. Figure 25-2A shows maxillary incisors that are

unequal in length because of wear. After orthodontic extrusion of the left

central incisor and incisal contouring, the teeth appear to be more equal in

length (Figure 25-2B). The ability to reposition both

bone and gingiva as the tooth moves is an attractive feature of orthodontic

treatment.

Figure 25-2A: Maxillary central incisors of equal length with lingual braces to extrude (bring down) the left central incisor, making the gingival margins the same height, and to close the spaces.

Figure 25-2B: After orthodontics. Note that the gingival margins of the central incisors are at the same level, and the incisal edges have been evened.

RETENTION

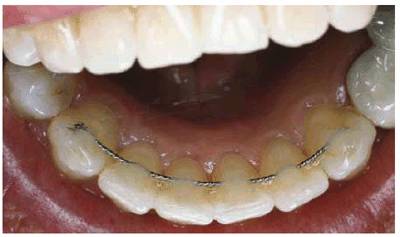

The importance of postorthodontic stabilization (retention) cannot be

overstated. Many adult patients seek treatment for esthetic problems that were

orthodontically treated years earlier but not retained past a few years.

Patients who seek re-treatment report that they simply stopped wearing

retainers a few years after completing orthodontic treatment and have had a

gradual regression in their tooth position. Patients must be motivated to wear

retainers at least occasionally throughout their adult years to prevent significant

tooth movement. The issue of patient compliance can be negated with fixed

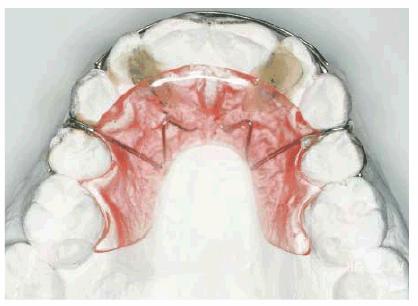

orthodontic retainers (Figures 25-3A 25-3B, and 25-3C). The major deficiency of fixed

retainers is the difficulty they present to the patient when flossing between

the teeth that hold the retainers. A patient who had difficulty with flossing

in general would not be a good candidate for fixed retention. The bonded

maxillary lingual retainer, in addition to causing flossing difficulties, could

also come in contact with the incisal edges of the mandibular anterior teeth

and may cause undesirable pressure on the anterior teeth of both arches.

Figure 25-3A: Bonded fixed lingual retainer on the maxillary central incisors placed prior to removal of labial braces to maintain a closed midline space.

Figure 25-3B: Bonded retainer designed to avoid a swollen gingival papilla.

Figure 25-3C: Bonded fixed lingual retainer on the lower anterior teeth.

CROWDED TEETH

Expansion Therapy: Nonextraction

Treatment

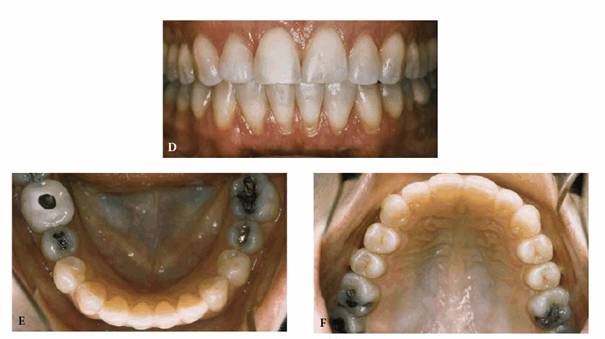

A moderate crowding with a Class II cuspid (Figure 25-4A) can be treated with a conservative

approach using the Crozat expansion appliance and bonded brackets (Figures 25-4B

and C 25-4D to F). An alternative treatment that

could achieve esthetic results would be a restorative option such as porcelain

laminate veneers. This would entail the removal of enamel and the challenge of

creating esthetic anterior restorations. The patient should be informed that

the additional benefit of orthodontic rather than restorative treatment in this

situation is avoidance of maintaining and/or replacing the veneers because of

chipping or gingival recession.

Figure 25-4A: Pretreatment view of a crowded constricted dentition. Note the constricted upper canines and the upper right canine directly on the lower canine (Class II).

Figure 25-4B and C: Occlusal views during treatment with Crozat removable appliances. Note the spaces that were created in the bicuspid regions through gradual expansion of the dental arches.

Figure 25-4D to F: Post-treatment views of the completed treatment. The dental midlines no longer meet, but tooth alignment and intercuspation of the posterior teeth have been improved.

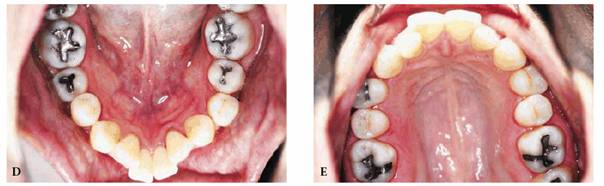

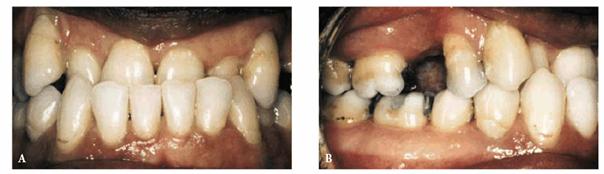

The patient in Figures 25-5A 25-5B, and 25-5C presented a more severely

constricted and crowded problem and was opposed to extracting any teeth. The

Crozat expansion appliance was placed for 18 months to create pressure against

the inside base of the posterior teeth. The amount of expansion achieved (Figures 25-5D

and E) was

sufficient to begin tooth alignment using direct bonded clear brackets (Figure 25-5F). The treatment was an esthetic

success, with all of the teeth in good alignment and the dental arches nicely

formed (Figures 25-5G to

I

Figure 25-5A: Preoperative anterior view with teeth apart to show incisal irregularities.

Figure 25-5B: Lower occlusal view showing extreme constriction and crowding and Crozat removable expander.

Figure 25-5C: Upper occlusal view with crowding and constriction.

Figure 25-5D and E: Upper and lower occlusal views after the Crozat appliance has expanded the width of the dental arches and created space for incisor alignment.

Figure 25-5F: Intraoral view of the teeth with direct bond brackets to align and detail the position of the teeth and refine the occlusion after Crozat expansion.

Figure 25-5G to I: Views of the completed treatment. Note the widened arch forms and reduced overjet.

Lower Crowding with Slight Underbite (Class

III) Figures 25-6A

and B 25-6C and D show a patient with more

significant crowding complicated by anterior crossbite and anterior open bite.

Lingual upper and clear lower braces were used to correct the problem.

Figure 25-6A and B: Intraoral views of lower crowding. Note the forward position of the lower right canine relative to the upper canine and the lack of overjet.

Figure 25-6C and D: Intraoral views of the corrected dentition with upper lingual and lower clear brackets. There is noticeable inflammation of the tissues near the lower incisors.

The Crozat appliance can create generalized expansion and sufficient intra-arch

space for tooth repositioning even in the severest cases (Figures 25-7A

and B 25-7C and D 25-7E and F). The completed treatment is shown

in Figures 25-7G to

I

Figure 25-7A and B: Pretreatment intraoral photographs of severe crowding resulting in incisor crossbite and uneven lower incisal height.

Figure 25-7C and D: Preoperative occlusal views of maxillary and mandibular arches.

Figure 25-7E and F: Occlusal photographs after expansion with the Crozat expansion appliance. Note the spaces in the premolar region. The patient is now ready for bonded brackets.

Figure 25-7G to I: Completed treatment prior to bracket removal.

When the

width of the maxillary and mandibular arches is insufficient to allow the teeth

to align without crowding (Figure 25-8) or there is a posterior crossbite

(Figure 25-9), a course of orthodontic therapy

should be undertaken to expand the deficient arches. The expansion will

diminish the negative smile space (dark spaces between the cheeks and the

bicuspids and molars) and create a more favorable environment for tooth

alignment and improved occlusion.

Figure 25-8: Severely constricted upper and lower dental arches causing crowding of the dentition and an inward tilt of the teeth and needing expansion.

Figure 25-9: Constricted upper dental arch causing posterior crossbite and posterior open bite and needing posterior upper expansion.

Class I Severe Crowding with Extractions

A routine procedure in orthodontic therapy was the extraction of permanent

teeth. This was largely because the profession was guided by early research

that considered a flat profile as the optimal esthetic result. This treatment

concept has been replaced by a less stringent desire for a flat profile and a

concern for possible negative side effects of bicuspid extractions. However, in

some cases, severe crowding cannot be resolved without extractions. Bicuspid

extractions were selected for the patient in Figure 25-10A to maintain the permanent

mandibular cuspids in the occlusal scheme. The final result (Figure 25-10B) was obtained with some consequence

to the gingiva of the mandibular cuspids. Note the labial gingival recession of

the left mandibular cuspid in comparison with the gingiva of the mandibular

right cuspid, which shows no change from the original height.

Figure 25-10A: Pretreatment intraoral photograph showing severe lower canine displacement and crowding.

Figure 25-10B: Post-treatment photograph after extraction of the four first bicuspids and treatment with clear orthodontic brackets. Note the gingival recession of the lower left canine.

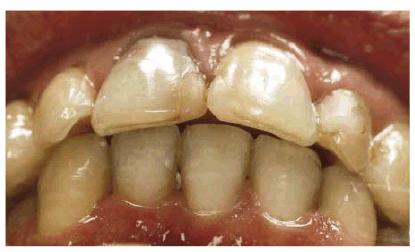

The unesthetic smile in Figures 25-11A

and B is

owing to the high position of the maxillary permanent cuspids. The natural

eruption of the cuspids was inhibited by the lack of space in the maxillary

arch. Extraction of the bicuspids was required to provide adequate space for

the cuspids. Esthetic combination bracket therapy (Figure 25-11C) using a lingual orthodontic

appliance on the anterior teeth and standard labial appliances on the posterior

teeth achieved the excellent esthetic results seen in Figures 25-11D

and E

Figure 25-11A and B: Unesthetic smile caused by misplaced maxillary canines.

Figure 25-11C: This photograph shows the canines moved into the bicuspid spaces with the orthodontic brackets behind the anterior teeth and on the labial surfaces of the posterior teeth.

Figure 25-11D and E: Facial and smile photographs near the completion of treatment.

DIASTEMA

Early Treatment

Figure 25-12A shows a patient with a large

maxillary midline diastema that is not only unesthetic but, more critically, is

also preventing the eruption of the maxillary lateral incisors. The treatment

consists of the bonding of orthodontic brackets to the maxillary central

incisors, placing a contoured rectangular arch wire, and using chain elastics

to draw the teeth together (Figures 25-12B, and 25-12C). This should all be held in

position until the maxillary lateral incisors are fully erupted (Figure 25-12D). After the maxillary lateral

incisors are completely erupted (Figure 25-12E), the patient is ready for

corrective orthodontics for the Class II right and midline correction.

Figure 25-12A: Large midline diastema preventing eruption of the lateral incisors.

Figure 25-12B: Early treatment initiated to close the space.

Figure 25-12C: Space closure completed.

Figure 25-12D: Lateral incisors erupting.

Figure 25-12E: After complete eruption of all permanent teeth and prior to initiation of orthodontic treatment to correct the overbite and Class II on the right side.

Diastema Correction

The patient in Figure 25-13A has a large midline diastema and a

severe overbite that would preclude retraction of the maxillary anterior teeth.

Retraction of the maxillary anterior teeth to close the space would cause

significant interference between the maxillary and mandibular incisors. Figure 25-13B shows the completed orthodontic

treatment with the ideal overbite and overjet.

Figure 25-13A: Large midline diastema complicated by a very deep overbite.

Figure 25-13B: Completed orthodontic treatment with corrected overbite.

Diastema Differential Diagnosis

Certain criteria must be evaluated when attempting to correct a maxillary

diastema in an adult patient:

. Is there sufficient overjet to retract the incisors to close the diastema

without interference from the mandibular incisors?

. Is the overbite sufficient to allow retraction of the anterior teeth without

contacting the mandibular incisors?

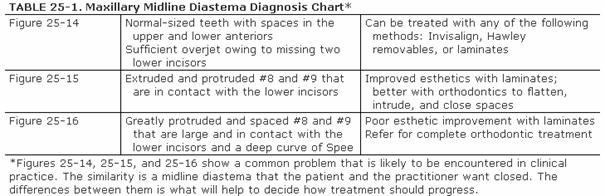

Criteria are compared in Table 25-1. These criteria were sufficiently

met in the patient in Figures 25-14A

and B, who

has a maxillary midline diastema and sufficient overjet with minimal overbite.

The maxillary anterior teeth can be retracted using a Hawley appliance or

maxillary braces alone without mandibular braces for bite opening.

Figure 25-14A and B: Midline diastema with sufficient overjet and minimal overbite to allow space closure with an upper Hawley.

Figure 25-15 shows a patient who has sufficient

overjet but too much overbite, which causes the mandibular incisors to contact

the lingual surface of the maxillary incisors. Retraction of the maxillary

teeth causes excess interference with the incisal edges of the mandibular

incisors. This case requires treatment with both maxillary and mandibular

braces for orthodontic space closure; a Hawley appliance would not be

sufficient for correction. The patient in Figures 25-16A

and B has

multiple maxillary anterior spaces that also require correction with

conventional orthodontics rather than a Hawley appliance because of the severe

overbite and overjet.

Figure 25-15: Maxillary midline diastema with sufficient overjet but upper incisal contact with the lower incisors preventing easy space closure.

Figure 25-16A and B: Upper spacing with severe overbite and overjet requiring comprehensive orthodontic treatment for space closure.

CROSSBITE

The decision to correct a dental crossbite rests on a number of factors:

. Is the crossbite anterior or posterior?

. Is it functional (ie, causes no problems) or harmful?

. If it is posterior unilateral, does it cause a mandibular shift to one side?

. Is it an esthetic problem?

. Is there a skeletal component, or is the problem limited to the teeth?

Not all crossbites require correction. Some crossbites cause no functional or

esthetic problems, such as an isolated first molar, and do not necessarily

require correction.

Posterior Crossbite

The diagnosis of a unilateral posterior crossbite involving all of the

posterior teeth on one side requires an analysis of the dental and facial

midlines. The occlusion shown in Figure 25-17A is an excellent example of a

mandibular shift caused by a constricted maxillary arch. Note how the

mandibular dental midline and the entire mandible (Figure 25-17B) are deviated 3 mm to the side of

the posterior crossbite. This patient deviates markedly to the left. This is a

diagnostic feature of a maxillary constriction that requires bilateral

maxillary expansion to correct. Once the maxilla is bilaterally expanded, the

mandibular midline will usually not shift. When diagnosing this situation, it

would have been easy to assume that the patient had only a unilateral

crossbite.

Figure 25-17A: Unilateral posterior crossbite with a marked midline discrepancy indicating there is a shift of the mandible. This means that the maxillary arch is most likely constricted on both sides.

Figure 25-17B: Facial view showing the mandibular shift to the left.

Anterior Crossbite

Diagnosis of an anterior crossbite, as depicted in Figures 25-18A

and B, is

augmented by the use of a cephalometric film that examines the basic underlying

skeletal pattern. In this case, a prognathic mandible (lower jaw more forward)

was diagnosed. The decision was made to extract the mandibular left and right

first bicuspids because the patient did not want orthognathic surgery to push

back the mandible. Orthodontic therapy resulted in space closure for both the

maxillary and mandibular arches and correction of the anterior crossbite (Figures 25-18C

and D

Figure 25-18A and B: Anterior crossbite and missing maxillary first bicuspids.

Figure 25-18C and D: Post-treatment results after extraction of the lower bicuspids and space closure of the missing teeth.

Short Lower Jaw (Class II, Division 2)

with Extrusion of the Maxillary Anterior Teeth

The maxillary anterior component of this particular malocclusion gives rise to

a number of esthetic factors in addition to the underlying Class II

interdigitation of the cuspids and posterior teeth. Among these are, in

particular, the lingual inclination of the maxillary central incisors and the

extrusion of the maxillary anterior teeth beyond the plane of occlusion. The

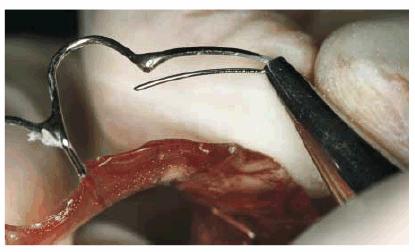

extrusion can produce a gummy smile (Figure 25-19A), which can be corrected through

orthodontic torquing and intrusion of the maxillary anterior teeth. Correction

requires the use of a full-bonded Edgewise orthodontic appliance with the

addition of a torquing auxiliary (Figure 25-19B) that will push back the roots of

the maxillary incisors and establish proper incisal inclination (torque). The

final result (Figures 25-19C

and D) shows

the maxillary incisors intruded to the level of the occlusal plane and a Class

I occlusion.

Figure 25-19A: Severe overbite and extrusion of the maxillary teeth combined with a Class II bite relationship. Note the backward angle (torque) of the upper anterior teeth and their position below the level of the occlusal plane.

Figure 25-19B: Torquing auxiliary to push back the roots of the upper anterior teeth.

Figure 25-19C and D: Completed treatment after intruding the upper anterior teeth and widening the arch in the premolar area.

Severe Overbite

Untreated overbite (Figure 25-20) will, in time, lead to severe wear

of the incisal edges of the mandibular and/or the maxillary teeth. This can

easily be overlooked unless the practitioner carefully observes the mandibular

anterior teeth in full centric occlusion. Once in this position, not more than

50% of the mandibular teeth should be covered by the maxillary incisors.

There are two distinct causes of excess anterior overbite that, when left

untreated, will cause excessive incisal wear:

Figure 25-20: Severe wear on the upper and lower anterior teeth caused by untreated overbite and bruxism.

. Extrusion of the maxillary incisors. This can be a significant cause

of a "gummy smile" because the gingival margins of the maxillary

central and lateral incisors are more incisally (lower) positioned than the

posterior buccal segments (see Figures 25-19A 25-21A and B). Intrusion with full fixed

orthodontic appliances is required to obtain better functional and esthetic

tooth position.

Figure 25-21A and B: Extrusion of the maxillary incisors below the level of the posterior teeth and the occlusal plane. Note the level of the upper incisal gingiva.

. Extrusion of the mandibular anterior quadrant (cuspid to cuspid). The

mandibular six anterior teeth are significantly higher than the posterior

teeth. Typically, the mandibular arch appears normal except for the fact that

there is a severe marginal ridge discrepancy between the cuspid and the first

bicuspid (see Figures 25-20, and 25-22A). Although the severe deep overbite

seems obvious, a dentist did not diagnose it until the patient was 35 years

old. After orthodontic treatment prior to restorative treatment, the

restorative dentist can create a more esthetic restorative result. Figure 25-22B shows the severity of the overbite.

Figure 25-22C shows the correction.

Figure 25-22A and B: Severe overbite with extrusion of the lower anterior teeth. Note extreme wear on lower incisors.

Figure 25-22C: Corrected overbite after orthodontic treatment.

Patients

with these problems routinely state that they were never informed by their

dentist that they had an overbite and were never advised to seek orthodontic

treatment. Figure 25-23 shows a subtle overbite that can

easily be overlooked by the general dentist. This should be treated with

appropriate orthodontic therapy; otherwise, if left untreated, excessive incisal

wear may result.

Figure 25-23: An easily overlooked overbite that needs correction.

INTERDISCIPLINARY TREATMENT

Many patients present with a variety of problems such as missing teeth,

drifting, crowding, malocclusion, and extrusion that require the intervention

of several dental disciplines. As dental professionals, we can never assume

what the patient will accept or reject as the appropriate esthetic treatment or

goal. The wise dentist develops a group of fellow practitioners of differing

specialties who can review the diagnostic work-up of a patient whenever there

is a question of potential issues that may compromise the final esthetic

result. Not only is it the best service we can provide to our patients, it is

also our responsibility to gather, analyze, and present all possible options

for treatment so that they can make informed decisions. Only the patient can

determine how much time, money, and effort that he or she is willing to invest,

as well as what is a personally esthetic result. These issues are discussed

more thoroughly in Chapter 2, "Esthetic Treatment Planning," Esthetics

in Dentistry, Volume 1, 2nd Edition; however, the following generalized,

comprehensive approach may be used as a sequence of interdisciplinary

treatment:

. Restorative and periodontal evaluation

. Orthodontic referral and evaluation

. Determination of an initial plan between the restorative dentist and/or the

periodontist (if necessary) and the orthodontist

. Removal of decay and infection

. Initiation of an orthodontic treatment plan

. Periodic consultations between the restorative dentist and the orthodontist

to evaluate progress and possible alterations to the treatment plan

necessitated by patient cooperation, infection, or difficulties in tooth

movement (not all teeth move as planned) during orthodontic treatment.

Increased periodontal monitoring is essential during adult orthodontic

treatment.

. Removal of braces and initiation of restorative treatment plan

. Orthodontic retention

Figure 25-24A depicts a patient who requires

interdisciplinary evaluation. Note the uneven spacing of the maxillary anterior

teeth and the small maxillary left lateral incisor. Figure 25-24B was the result of efforts of the

following specific dental disciplines:

.

Soft-tissue management

. Orthodontics

. Implant prosthodontics (sometimes started during orthodontics)

. Fixed prosthodontics

. Removable prosthodontics

Figure 25-24A: A case that will require the talents of several dental disciplines to achieve an esthetic and functional result. Note the missing tooth #7, spacing missing posterior teeth.

Figure 25-24B: After orthodontics and completed restorative treatment with crowns, implants, and a removable prosthesis.

ESTHETIC FORMS OF ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT

Computer-Assisted Treatment Trays

(Invisalign)

The search for an esthetic method of repositioning teeth has been ongoing. If

patients can have an esthetically acceptable method of repositioning their

teeth, they can more easily be motivated to accept an ideal treatment plan that

includes orthodontics. An innovative orthodontic corrective procedure was

introduced in 1999 that uses a series of clear, removable, hard acrylic trays

similar to bleaching trays. A computer program designs the orthodontic

correction in a series of stages similar to the numerous drawings of animated

cartoons. For each of these stages of tooth movement, a single acrylic tray is

made. The patient wears this tray for 2 to 3 weeks to accomplish a small amount

of tooth movement. There may be as few as 5 or as many as 60 stages, depending

on the complexity of the problem. Careful and constant supervision is required,

particularly because patient compliance is more of a factor for success than in

most other orthodontic techniques. Figures 25-25A

and B show a

typical case that falls within the guidelines for successful treatment with

computer-assisted tray therapy. Beyond the patient compliance factor, the

several situations that are unsuitable for computer-assisted therapy include

the following:

. When teeth are still erupting

. When extractions are required

. When a correction will be greater than 4 mm

. An overbite greater than 50%

. Crowding greater than 6 mm to be corrected to ideal

. Impacted teeth that need to erupt

. When severely tipped teeth must be uprighted

. When severely rotated cuspids and bicuspids require correction

. When tooth extrusion or intrusion greater than 3 mm is required

. When cuspids or molars require more than 3 mm to achieve a Class 1 occlusion

. Surgical-orthodontic cases

. Treatment of temporomandibular joint problems

Figure 25-25A and B: Before and after treatment with removable tray therapy in which the lower incisors were aligned.

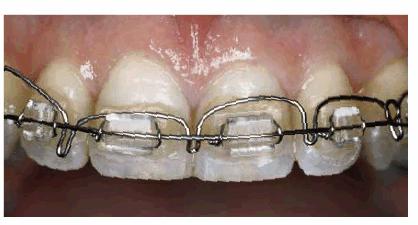

Lingual Appliance Therapy

Lingual orthodontic therapy was introduced as an esthetic alternative to

conventional braces. There are a few limitations for lingual appliance therapy,

particularly concerning the technical demands on the orthodontist when bending

the finishing wires. There is an increased amount of patient "chair

time" and an associated increased cost factor that can limit the use of

the appliances. Also, some cases must be completed with labial appliances.

However, almost every type of malocclusion can be treated with lingual braces.

The patient in Figure 25-26A desired a flattening of her

profile. She had four first bicuspids removed, lingual braces placed on the

maxillary teeth (Figures 25-26B

and C), and

clear braces placed on her mandibular teeth to reduce treatment cost. Acrylic

pontics were bonded onto the mesial surface of the maxillary second bicuspids

to help mask the space from the missing bicuspids until the anterior teeth

could be retracted. As the space closed, the pontics were trimmed to allow

continued tooth movement.

Figure 25-26A: Profile view of a patient wishing reduction of a protrusive profile.

Figure 25-26B and C: Treatment photographs after removal of the first bicuspids and placement of pontics in the upper extraction spaces to minimize the visual impact of the extractions.

Removable Appliance Therapy

Many perspective orthodontic patients are interested in correcting their

problems with a "retainer." These patients are referring to the

removable Hawley appliance that, for decades, has helped countless patients who

would not wear fixed appliances. The patient in Figures 25-27A, and 25-27B requires limited tooth

repositioning, and a "retainer" with springs that tuck in the mesial

surface of the lateral incisors was selected. A diamond disk removes sufficient

enamel from both sides of the lateral incisor (Figure 25-27C) to allow the teeth to move in the

desired manner. The important issue here is to remove the enamel completely to

the gingival margin so that the enamel is not touching the adjacent teeth,

preventing the intended movement. The appliance was made with wax in the area

of tooth movement (behind the mesial surface of the lateral incisors) so that

tooth movement would not be prevented by any acrylic on the appliance (Figure 25-27D

Figure 25-27A: A problem ideally suited for treatment with a Hawley appliance; rotated upper lateral incisors that have sufficient overjet to allow for tooth movement.

Figure 25-27B: Rotation springs are activated to apply pressure to the desired tooth surface when the appliance is in the mouth.

Figure

25-27C: Interproximal tooth reduction is accomplished on the mesial and distal

surfaces down to the gingival margin to ensure that there is no enamel still in

contact that would prevent tooth movement. A diamond stone (DET-GF, Brasseler,

Figure 25-27D: Waxing the model to prevent acrylic from contacting the mesiolingual surface of the teeth to be moved.

Another example of limited tooth movement is shown in Figures 25-28A and 25-28B. The lateral incisor has rotated

outward and will be corrected with a Hawley appliance and a finger spring.

Indications for this appliance are small rotations of anterior teeth, anterior

spaces, and limited tooth tipping. Limitations are rotated posterior teeth,

posterior spaces, bite correction, and maxillary midline diastemata when the

mandibular incisors contact the maxillary incisors.

Figure 25-28A: Appliance in place to move in the mesial surface of the lateral incisor; note the large space between the mesial surface of the lateral and the appliance.

Figure 25-28B: Treatment almost completed. Sufficient enamel has been removed from the lateral incisor to allow it to fit into a smaller space.

CONCLUSION

When patients can consider two or more treatment options (that include

different appliances, time frames, costs, and, possibly, outcomes), they are

more likely to accept treatment. Surprisingly, it will sometimes even be full

metal brackets for a rather long duration. In any event, both general or

esthetic dentists and orthodontists are urged to incorporate flexibility and

compromise in their treatment plans. Contemporary dental patients expect

esthetic appliance options, and, regardless of the final treatment choice,

everyone benefits when patients are able to make informed decisions. The

available treatment methods presented here all have a place in the esthetic

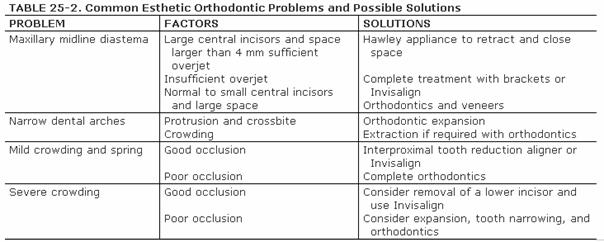

orthodontic care of our patients. A summary of problems and solutions are

presented in Table 25-2. Any dental problem that requires

better tooth position for a better esthetic restorative result should have an

orthodontic consultation.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Azizi M, Shrout MK, Haas AJ, et al. A retrospective study of angle Class I

malocclusions treated orthodontically without extraction using two palatal expansion

methods. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 1999;116:101-7.

Bishara SE, Ortho D, Jakobsen JR. Profile changes in patients treated with and

without extractions: assessments by lay people. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1997;112:639-43.

Brightman B, Hans MG, Wolf GR, Bernard H. Recognition of malocclusion: an

education outcomes assessment. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1999;116:444-51.

Cowan R Jr. Treatment of a patient with a Class II malocclusion, impacted

canine, and severe malalignment. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 2000;118:693-8.

Derakhshan M, Sadowsky C. A relatively minor adult case becomes significantly

complex: a lesson in humility. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 2001;119:546-53.

Fujuita K. New orthodontic treatment with lingual bracket mushroom arch wire

appliance. Am J Orthod

1979;76:657.

Goldstein MC. Adult orthodontics. Am J Orthod 1958;39:400.

Goldstein MC. Adult orthodontics and the general practitioner. J Can Dent Assoc

1958;23:261.

Goldstein MC. Orthodontics in crown and bridge and periodontal therapy. Dent

Clin North Am 1964; July:449-59.

Goldstein MC, Fritz ME. Treatment of periodontosis by combined orthodontic and

periodontal approach. J Am Dent

Assoc 1976;93:985.

Goldstein R. Dental esthetics.

Hemmings KW, Darbar UR, Vaughan S. Tooth wear treated with direct composite

restorations at an increased vertical dimension: results at 30 months. J Prosthet

Dent 2000;83:287-93.

Klontz HA. Facial balance and harmony: an attainable objective for the patient

with a high mandibular plane angle. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1998;114: 176-88.

Kurz C. The use of lingual appliances for correction of bimaxillary protrusion.

Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1997;112:357-63.

Laino A, Melsen B. Orthodontic treatment of a patient with multidisciplinary

problems. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1997;111:141-8.

Miller RJ. Invisalign: current application and future direction. Presented at

the 101st Annual Session of the AAO,

Newman GV. Current status of bonding attachments. J Clin Orthod 1973;7:7.

Oliva de Cuebas J. Nonsurgical treatment of a skeletal vertical discrepancy

with a significant open bite. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1997;112:124-31.

Pearson L. Rapid maxillary expansion with incisor intrusion: a study of

vertical control. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1999;115:576-82.

Pintado M. Variation in tooth wear in young adults over a two-year period. J

Prosthet Dent 1997;77:317-20.

Poling R. A method of finishing the occlusion. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1999;115:476-87.

Rivera SM, Hatch JP, Dolce C, et al. Patients' own reasons and

patient-perceived recommendations for orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 2000;118:134-40.

Sarver DM, Ackerman JL. Orthodontics about face: the re-emergence of the

esthetic paradigm. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 2000;117:575-6.

Shue-Te Yeh M, Koochek A-R, Vlaskalic V, et al. The relationship of 2

professional occlusal indexes with patients' perceptions of aesthetics,

function, speech, and orthodontic treatment need. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 2000;18:421-8.

Smith BG, Bartlett DW,

Smith SW, English JD. Orthodontic correction of a Class III malocclusion in an

adolescent patient with a bonded RPE and protraction face mask. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1999;116:177-83.

Tung AW, Kiyak A. Psychological influences on the timing of orthodontic

treatment. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1998;113:29-39.

Wilson JR. Treatment of a Class II, Division 2 malocclusion with one

congenitally missing and one malformed lateral incisor and a palatally impacted

maxillary canine. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;114:55-9.

|