Ancient Indications of Angling and Ethics

By Jon

Lyman

|

|

|

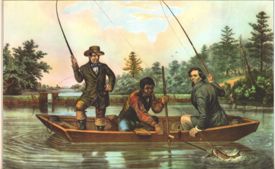

"I believe I have you

now, sir: Daniel Webster's great trout,": a

painting from the 1850s of fly fishermen.

|

Humans have been fishing

for sport as well as food for almost as long as fishing has existed. In Europe, angling for pleasure can be traced back to the

first century A.D. In the Far East, sport

fishing - with bamboo rods, silk lines, flies, and barbless

hooks - dates back more than 3,000 years.

Parallel to this long history of sport angling are signs of the development of

angling ethics. There were very early discussions about the need to limit one's

catch. Releasing fish alive may be nearly as old as the sport itself.

In the 1950s and '60s, state fish and wildlife agencies brought the weight of

science to bear on the problem of renewing and sustaining wild fish

populations. In recent decades, agencies have focused on developing a mix of

management practices to ensure the health of fish populations while providing

angling opportunities. Catch and release was formalized as one management tool

through extensive research.

Some fisheries managers have said that "Fishing for Fun" began in the 1950s as

a pseudonym for the first catch and release fisheries. Some fly fishers

maintain that catch and release began with Lee Wulff's

1939 admonition that "a sport fish is too valuable to be caught only once." But

catch and release is far more ancient in origin and practice.

From Martial's poetry of the first century to Sir

Humphrey Davy's "Salmonia" in 1829, anglers

have written about the need to release a portion of their catch. In 23523c220x America, the

earliest discussion of the need to conserve resources and release fish comes

with our first great author on fishing, Thaddeus Norris. His "The American

Angler," published in 1864, was the first book published in the United States

wholly written by an American angler about our fisheries. Uncle Thad, as Norris

came to be known, wrote about the destruction of our fisheries and the need for

resource conservation. He also wrote of releasing as many fish as he kept.

Perhaps the most influential book in the conservation movement of the early

years after the Civil War was written by a Boston minister named William Henry Harrison

Murray. "Adirondack Murray", as he was known, published his "Adventures in

the Wilderness" in 1869. The book went through eight printings in its

first year and led to the building of over 200 "Great Camps" in the Adirondacks within five years. "Murray's

Fools" flooded the wilderness from the East Coast through the Midwest

each weekend, packing specially scheduled railroad trains which ran from urban centers to wild places. This was the birth of industrial

tourism that we experience in Alaska

today.

Murray wrote of

the need to restrict one's harvest of fish and game to that which is needed for

food, and of releasing fully half of his catch. In the final 20 years of the

19th century, editors of outdoor magazines championed releasing fish as a means

of conservation. By the time of the "Golden Age" of fly fishing, during the

first several decades of the 20th century, catch and release was well

established as part of the ethics of responsible angling. Just a few quotes

from some of the more prominent writers of the day will illustrate this.

Theodore Gordon, perhaps the most revered angling writer at the turn of the

last century, remarked in 1905 on the growing practice of releasing fish. "Some

say it is well to kill off the big fish. I doubt this greatly" and "I know Mr. LaBranche by reputation, and his ideals are high. He fishes

the floating fly only and kills a few of the large trout. All others are

returned to the water.... I fancy that a trout should be big enough to take

line from the reel before it is considered large enough to kill."

|

|

|

"Murray's

Fools" Author and minister William Murray inspired thousands of urban

dwellers to visit the outdoors in the late 1800s.

|

In "Streamcraft" (1919), George Parker Holden took time

out from describing the habits and lures of trout and bass to declare "not the

least of the beauties" of fly fishing is that the quarry is hooked "lightly

through the lip." Holden then instructed on how to release fish easily, with

minimal damage. He quoted Harold Trowbridge, from Outlook magazine, Aug. 6,

1919, extensively on the use of barbless hooks. Here

was perhaps the first documented example of catch and release with no intent to

harvest:

"In one morning's fishing out of fifty successive fish which I hooked I found

it necessary to take only three out of the water in order to release them from

the line. Two dropped off as they came over the side of the boat, and only one

required an instant's touch before the hook could be slipped from its jaw."

Holden declared: "Do not be afraid to join the slowly growing fraternity of

those anglers whose password is 'We put'em back alive!'"

Hewitt's "Handbook of Fly Fishing" (1933) touched briefly on

releasing fish: "It is surprising what freedom and relief one feels when the

basket is left home. I rarely carry one any more, as I seldom kill more than

one or two fish for a day's sport, knowing only too well how long it takes to

grow these fish and how few of them are in any stream. I do not want to injure

my own sport or the sport of others in future."

In 1936, Gifford Pinchot published "Just Fishing

Talk." He referred repeatedly to releasing fish.

"We love the search for fish and the finding, the tense eagerness before the

strike and the tenser excitement afterward; the long hard fight, searching the

heart, testing the body and soul; and the supreme moment when the glorious

creature, fresh risen from the depths of the sea, floats to your hand and then,

the hook removed, sinks with a gentle motion back from whence it came, to live

and fight another day."

These writings and many others led to Lee Wulff's

famous declarations in 1939 "Game fish are too valuable to be caught only

once," and "The fish you release is your gift to another angler and remember,

it may have been someone's similar gift to you."

A Brief Catskill Angling History

By Roger Menard

(Roger

Menard is the author of the new book, My

Side of the River: Reflections of a Catskill Fly Fisherman. Mr. Menard will be a featured participant of the MTHS special program

A CELEBRATION OF CATSKILL MOUNTAIN FLY FISHING, April 6 from 1:00 to

4:00 pm at the Windham Civic Center, featuring

demonstrations of fly tying and casting, a slide show, historical and art

exhibits, and a book signing with Mr. Menard.)

Angling history has been

recorded for hundred of years. Fly fishing history, largely European, followed

suit. Cumulative over time, information on tackle, knowledge of anglers,

intimate knowledge of rivers and local lore all add to the history of fly

fishing.

Historically, New York State's Catskill Mountains

capture a unique position in the annals of American fly fishing. The Catskills

have the distinction of being the birthplace of the American dry fly. It was

here in the late 1800s that Theodore Gordon, a Catskill writer and angler,

after much overseas correspondence with Mr. F. Halford,

a leading British authority, developed dry flies suitable for the fast flowing

rivers of the Catskills. His signature fly, the Quill Gordon, remains a basic

pattern for eastern anglers. Right next to the Quill Gordon is the very popular

Hendrickson, tied by Roy Steenrod, an acquaintance of

Gordon's.

Over the years, a legion of resident fly tyers

following Gordon's footsteps became the nucleus of the Catskill school of fly tyers. They included

Harry and Elsie Darbee, Walt and Winnie

Dette, Reub Cross, and

Herman Christian. Their skills gained popularity on the Beaver Kill and Neversink rivers of the western Catskills. Towards the

eastern side of the mountains, Preston Jennings and Ray Smith were tying flies

and catching trout on the Esopus. Art Flick, an

intrepid angler and fly tyer who owned the Westkill Tavern in Greene County,

was familiar with the waters of the Schoharie Creek. He also wrote a little

book on Catskill flies that still remains a classic for anglers wishing to

familiarize themselves with popular patterns.

Visiting anglers from large metropolitan areas were eager to bring

fine reels imported from England,

the best Spanish silkworm gut leaders, and quality hand-tied American flies to

match wits with wily Catskill trout. Classic bamboo rods have also contributed

to Catskill angling lore. The William Mills Company in New York City, agents

for the H.L. Leonard Rod Company and the E.F.Payne

Rod Company (both rods were made in Central Valley, New York), offered anglers

an array of split-bamboo fly rods to cast over their favorite

waters. Several rods were river-tested in the Catskills, and a few models were

named after the region.

In the mid-1800s, the coming of the Ulster

and Delaware and Ontario and Western railroads to the

Catskills opened up new horizons for visiting sportsmen. Fishing towns,

boarding houses, and hotels sprung up throughout the Catskills. For over one

hundred years notable anglers visiting the region read like a veritable

"Who's Who" of fishing fame. Angling writers Hewitt, LaBranche, McClane, Zern, Wulff, and Sparse Gray

Hackle led the way.

Fishing was good, too good, and the heavy baskets of trout, along

with increasing pollution, were beginning to take their toll on the rivers.

Brook trout require cold, pure water for survival. Excessive timbering and the

denuding of the mountains changed river channels and caused heavy silting.

Warming water temperatures were devastating to the eastern brook trout.

Things looked bleak. Fears were growing among anglers that trout

fishing would become a sport of the past. Then, a significant breakthrough

occurred. In the late 1800s brown trout were imported from Europe

and planted in Catskill waters. Being more tolerant of warmer stream

temperatures, they also had a good reputation for rising to the fly. In

addition, native west coast rainbow trout were transported to eastern waters.

The rainbows quickly adapted to the Esopus Creek. It

didn't take long for rainbow stocks to spawn naturally. Even today, rainbow

trout still fare well in the Esopus and its

tributaries.

New York City's

watershed, with its myriad of reservoirs, has also had its impact on fly

fishing. The Ashokan Reservoir, built in the early

1900s, has been a haven for large rainbow and brown trout. The cold water

discharge at the portal in Allaben (water transported

via a tunnel from the Schoharie Reservoir) enhances the quality of the Esopus and contributes to the natural reproduction of its

trout population. It is a great nursery river. There is also a migratory run of

browns and rainbows in the fall of the year.

The tailwater releases below the dams of

the reservoirs have been beneficial to both trout and insect populations,

creating first-rate fisheries.

The Catskills have enjoyed worldwide fame for over one hundred

years as an ideal place to fly fish, and that reputation continues today. With

care and nurturing, there is no reason why the Catskill rivers

shouldn't lure sportsmen for another hundred years, and even much, much longer.

Roger Menard is a resident of Ulster

County's Catskill

Mountains. He was a charter director of the Theodore Flyfishers and is a member of the Catskill Fly

Fishing Center and Museum, the

Catskill Fly Tyers Guild, and Trout Unlimited. A

conservationist, he was instrumental in obtaining "artificial

lure-only" regulations on the Amawalk

River in southern New York. An avid fly tyer,

he has sat alongside the vises of his friends Harry

and Elsie Darbee, Keith Fulsher,

Charlie Krom, Herb Howard, and Matt Vinceguerra. Besides fly fishing his home waters of the

Catskills and Adirondacks, his angling travels have taken him to the western

rivers of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming as well as to the Atlantic Canadian

Province of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Quebec.

|

PETITE HISTOIRE DE LA PECHE

|

|

|

| |

|

|

La pêche se fond dans

la nuit des temps. A l'aube de l'humanité, la pêche et la chasse se confondent.

Javelots

lances et harpons sont utilisés. L'homme préhistorique cherche ensuite attraper

des poissons plus petits

en les capturant la

main. La pêche se sépare tout jamais de la chasse. Le pêcheur ne frappe plus vue, mais

attire vers lui et ferre une proie

grâce un appât. L'homme invente, il y a 16000 ans, la ligne main. Fabriquée en liane, tendon ou racine,

elle est pourvue d'un hameçon très rudimentaire fait d'un

simple bâtonnet de bois ou

d'os, de fragments de silex

en forme de losange ou de croissants. A l'âge de la pierre polie, l'hameçon devient un crochet d'os, d'ivoire

ou de bois. Les hameçons,

tels que nous les connaissons aujourd'hui, pointent leur ardillon l'âge du

bronze. L'avènement du fer apporte l'hameçon

en fer qui a l'inconvénient de rouiller. Il faut attendre l'étamage (invention gauloise du début de notre ère) pour lutter contre la rouille. L'industrie de l'aiguille au XIXème siècle amène un grand essor dans la fabrication des hameçons. Les premières cannes

pêche que l'on utilise depuis la rive sont répertoriées dans des poèmes homériques des Egyptiens (2000 ans avant JC). La pêche n'est pas seulement alimentaire mais se pratique en loisir par les hautes classes. Les Egyptiens inventent toutes sortes de filets et de nasses (épuisette, senne, carrelet.). La pêche se fond dans

la nuit des temps. A l'aube de l'humanité, la pêche et la chasse se confondent.

Javelots

lances et harpons sont utilisés. L'homme préhistorique cherche ensuite attraper

des poissons plus petits

en les capturant la

main. La pêche se sépare tout jamais de la chasse. Le pêcheur ne frappe plus vue, mais

attire vers lui et ferre une proie

grâce un appât. L'homme invente, il y a 16000 ans, la ligne main. Fabriquée en liane, tendon ou racine,

elle est pourvue d'un hameçon très rudimentaire fait d'un

simple bâtonnet de bois ou

d'os, de fragments de silex

en forme de losange ou de croissants. A l'âge de la pierre polie, l'hameçon devient un crochet d'os, d'ivoire

ou de bois. Les hameçons,

tels que nous les connaissons aujourd'hui, pointent leur ardillon l'âge du

bronze. L'avènement du fer apporte l'hameçon

en fer qui a l'inconvénient de rouiller. Il faut attendre l'étamage (invention gauloise du début de notre ère) pour lutter contre la rouille. L'industrie de l'aiguille au XIXème siècle amène un grand essor dans la fabrication des hameçons. Les premières cannes

pêche que l'on utilise depuis la rive sont répertoriées dans des poèmes homériques des Egyptiens (2000 ans avant JC). La pêche n'est pas seulement alimentaire mais se pratique en loisir par les hautes classes. Les Egyptiens inventent toutes sortes de filets et de nasses (épuisette, senne, carrelet.).

|

|

|

|

AU FIL DE L'EAU ET

DU TEMPS

Dans la Grèce Antique, la

pêche est décriée au profit de la chasse, activité

prestigieuse, plus virile qui endurcit

et glorifie le guerrier.

Il faut attendre 5 siècles avant notre ère, pour que les Grecs devenus navigateurs, apprécient le poisson. La pêche au mort manié est utilisé chez les Grecs du IIème

siècle pour capturer le mérou.

La mouche artificielle est mentionnée dès le IIIe siècle, en Macédoine. Les pêcheurs remarquent que les poissons affectionnent un

certain type de mouche très

fragile. Ils la remplacent

en enveloppant l'hameçon

de laine écarlate laquelle ils

attachent deux plumes de

coq couleur de cire.

Néanmoins, 1500 avant J.C, les Crétois sont eux de fameux pêcheurs. Tandis que les Romains estiment la pêche comme digne moyen

d'occupation d'un homme libre qui développe la perspicacité et incite la méditation.

Quelques siècles plus tard, au Moyen-Age, la pêche est réglementée

en France

par une série d'ordonnances royales. La pêche la ligne

est pour les roturiers un moyen de subsistance appréciable. Mais, elle est

soumise de nombreuses restrictions. Le prélèvement

du poisson est le privilège des confréries agréées, des prêtres et des aristocrates.

|

|

Un premier traité de pêche

"Treatyse of Fisshung

with an Angle"est imprimé

en 1496 en Angleterre. Attribué

Dame Juliana Berners, il répertorie les poissons, le matériel de pêche, les appâts, les

techniques, des mouches. Un ouvrage,

daté de 1653, le "Pêcheur

la ligne" d'Izaac Walton expose différentes

techniques de pêche et présente

12 mouches artificielles.

Le premier moulinet la mouche, appelé dévidoir, est mentionné en 1653.

En 1789, la Révolution donne le même droit de pêche aux manants qu'aux autres catégories sociales. En Angleterre, la pêche la mouche artificielle

devient le seul sport halieutique digne d'un

gentleman. En 1789, la Révolution donne le même droit de pêche aux manants qu'aux autres catégories sociales. En Angleterre, la pêche la mouche artificielle

devient le seul sport halieutique digne d'un

gentleman.

Au XXème siècle, la pêche

rejoint la chasse et souffre

moins des préjugés. Des progrès techniques font évoluer

la pêche, comme le moulinet frein

incorporé en 1913 ou le moulinet tambour fixe en 1930.

Après la Seconde Guerre Mondiale,

la pêche se transforme.

Le pêcheur devient

voyageur, la pêche se mute en sport et en loisir.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| | | | |