![]()

Many private traders keep their market opinions to themselves, but financial journalists and market letter writers spew them forth like open fire hydrants. Some writers are very bright, but both groups as a whole have poor trading records.

Financial journalists and letter writers overstay important trends and miss major turning points. When these groups become bullish or bearish, it pays to trade against them. The behavior of groups is more primitive than individual behavior.

Consensus indicators, also known as contrary opinion indicators, are not as exact as trend-following indicators or oscillators. They simply draw your attention to the fact that a trend is ready to reverse. When you get that message, use technical indicators for more precise timing.

As long as the market crowd remains in conflict, the trend can continue. When the crowd reaches a strong consensus, the trend is ready to reverse. When the crowd becomes highly bullish, i 515f513f t pays to get ready to sell. When the crowd becomes strongly bearish, it pays to get ready to buy.

The

foundations of the contrary opinion theory were laid by Charles Mackay, a

Scottish barrister. He described in his book, Extraordinary Popular

Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, crowd behavior during the Dutch

Tulip Mania and the South Seas Bubble in

Abraham W.

Cohen, a

Tracking Advisory Opinion

Some letter writers are very smart, but taken as a group they are no better than average traders. They become very bullish at major tops and very bearish at major bottoms. Their consensus is similar to that of the trading crowd.

Most letter writers follow trends because they are afraid to appear foolish and lose subscribers by missing a major move. The longer a trend continues, the louder letter writers bay at it. The advisors are most bullish at market tops and most bearish at market bottoms. When most letter writers become strongly bullish or bearish, it is a good idea to trade against them.

Several rating services track the percentage of bulls and bears among advisors. The main rating services are Investors Intelligence in the stock market and Market Vane in the futures markets. Some advisors are very skilled at doubletalk. The man who speaks from both sides of his mouth can later claim that he was right regardless of the market's direction. Editors of Investors Intelligence and Market Vane have plenty of experience pinning down such lizards. As long as the same editor does the ratings, they remain internally consistent.

Investors Intelligence

Investors Intelligence was founded by Abe Cohen in 1963. He died in 1983, and his work is being continued by Michael Burke, the new editor and publisher. Investors Intelligence monitors about 130 stock market letters. It tabulates the percentage of bulls, bears, and fence-sitters among letter writers. The percentage of bears is especially important because it is emotionally hard for stock market writers to be bearish.

When the percentage of bears among stock market letter writers rises above 55, the market is near an important bottom. When the percentage of bears falls below 15 and the percentage of bulls rises above 65, the stock market is near an important top.

Market Vane

Market Vane rates about 70 newsletters covering 32 markets. It rates each writer's degree of bullishness in each market on a 9-point scale. It multiplies these ratings by an estimated number of subscribers to each service (most advisors wildly inflate those numbers to appear more popular). A consensus report on a scale from 0 (most bearish) to 100 (most bullish) is created by adding the ratings of all advisors. When bullish consensus approaches 70 percent to 80 percent, it is time to look for a downside reversal, and when it nears 20 percent to 30 percent, it is time to look to buy.

The reason for trading against the extremes in consensus is rooted in the structure of the futures markets. The number of contracts bought long and sold short is always equal. For example, if open interest in gold is 12,000 contracts, then 12,000 contracts are long and 12,000 contracts are short.

While the number of long and short contracts is always equal, the number of individuals who hold them keeps changing. If the majority is bullish, then the minority, those who are short, has more contracts per person than the longs. If the majority is bearish, then the bullish minority has bigger positions per person. The following example illustrates what happens when the consensus changes among 1000 traders who hold 12,000 contracts in one market.

![]() Open Bullish Number

of Number of Contracts Contracts

Open Bullish Number

of Number of Contracts Contracts

Interest Consensus Bulls Bears per Bull per Bear

![]() 500

500

800 200

200 800

![]() 1. If bullish

consensus equals 50 percent, then 50 percent of traders are long and 50

percent are short. An average trader who is long holds as many contracts as an

average trader who is short.

1. If bullish

consensus equals 50 percent, then 50 percent of traders are long and 50

percent are short. An average trader who is long holds as many contracts as an

average trader who is short.

The

opinions of market advisors serve as a proxy for the opinions of the entire market crowd. The best time to buy is when

the crowd is bearish, and the best time to go short is when the crowd is

bullish. The levels of bullishness at

which to buy or sell short vary from market to market. They need to be

adjusted every few months.

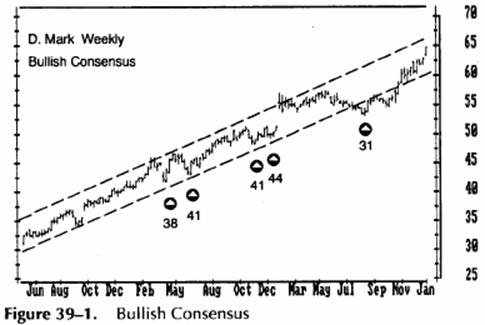

This weekly chart shows a bull market in the D. Mark, steadily moving up between a trendline and a parallel channel line. Whenever bullish consensus fell below 45 percent during this bull market, it gave a buy signal. The lower the bullish consensus, the more explosive the subsequent rally!

![]() When

bullish consensus reaches 80 percent, it shows that 80 percent

When

bullish consensus reaches 80 percent, it shows that 80 percent

of traders are long and 20 percent are short. Since the sizes of total

long and total short positions are always equal, an average bear is

short four times as many contracts as are held long by an average bull.

This means that an average bear has four times more money than an

average bull. The big money is on the short side of the market.

When bullish consensus falls to 20 percent, it means that 20 percent of traders are long and 80 percent are short. Since the numbers of long and short contracts are always equal, an average bull holds four times more contracts than are held by an average bear. It shows that big money is on the long side of the market.

Big money did not grow big by being stupid. Big traders tend to be more knowledgeable and successful than average - otherwise they stop being big traders. When big money gravitates to one side of the market, think of trading in that direction.

To interpret bullish consensus in any market, obtain at least twelve months of historical data on consensus and note the levels at which the market has turned in the past (Figure 39-1). Update these levels once every three months. The next time the market consensus becomes highly bullish, look for an opportunity to sell short using technical indicators. When the consensus becomes very bearish, look for a buying opportunity.

Advisory opinion sometimes begins to change a week or two in advance of major trend reversals. If bullish consensus ticks down from 78 to 76, or if it rises from 25 to 27, it shows that the savviest advisors are abandoning what looks like a winning trend. This means that the trend is ready to reverse.

Signals from the Press

To understand any group of people, you must know what its members want and what they fear. Financial journalists want to appear serious, intelligent, and informed; they are afraid of appearing ignorant or flaky. It is normal for financial journalists to straddle the fence and present several sides of every issue. A journalist is safe as long as he writes something like "monetary policy is about to push the market up, unless unforeseen factors push it down."

Internal contradiction is the normal state of affairs in financial journalism. Many financial editors are even bigger cowards than their writers. They print contradictory articles and call this "presenting a balanced picture."

For example, a recent issue of Business Week had an article headlined "The Winds of Inflation Are Blowing a Little Harder" on page 19. The article stated that the end of a war was likely to push oil prices up. Another article on page 32 of the same issue was headlined "Why the Inflation Scare Is Just That." It stated that the end of a war was going to push oil prices down.

Only a powerful and long-lasting trend can lure journalists and editors down from their fences. This happens when a wave of optimism or pessimism sweeps the market at the end of a major trend. When journalists climb down from the fence and express strongly bullish or bearish views, the trend is ripe for a reversal.

This is also the reason why the front covers of major business magazines are good contrarian indicators. When Business Week puts a bull on its cover, it is usually a good time to take profits on long positions in stocks, and when a bear graces the front cover, a bottom cannot be too far away.

Signals from the Advertisers

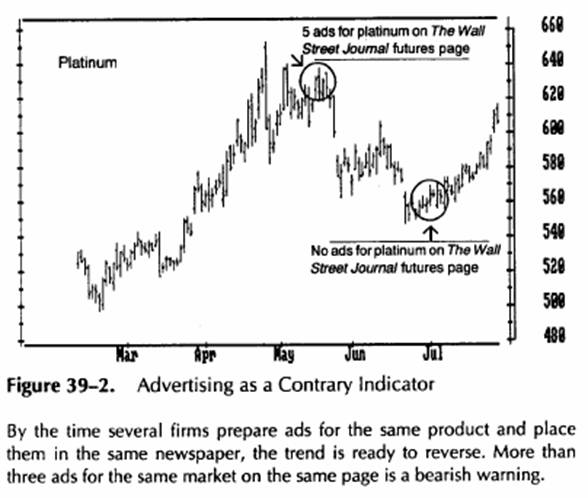

A group of three or more ads touting the same "opportunity" on the same page of a major newspaper often warns of a top (Figure 39-2). Only a well-established uptrend can break through the inertia of several brokerage firms. By the time all of them recognize a trend, come up with trading recommendations, produce ads, and place them in a newspaper, that trend is very old.

The ads on the commodities page of the Wall Street Journal appeal to the bullish appetites of the least-informed traders. Those ads almost never recommend selling; it is hard to get amateurs excited about going short. When three or more ads on the same day day tout opportunities in the same market, it is time to look at technical indicators for shorting signals.

Several government agencies and exchanges collect data on buying and selling by several groups of investors and traders. They publish summary reports of actual trades-commitments of money as well as ego. It pays to trade with those groups that have a track record of success and bet against those with poor track records.

For example, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) reports long and short positions of hedgers and big speculators. Hedgers - the commercial producers and consumers of commodities - are the most successful participants in the futures markets. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) reports purchases and sales by corporate insiders. Officers of publicly traded companies know when to buy or sell their company shares. The New York Stock Exchange reports the number of shares bought, sold, and shorted by its members and by odd-lot traders. Members are more successful than small-time speculators.

Commitments of Traders

Traders must report their positions to the CFTC after they reach certain levels, called reporting levels. At the time of this writing, if you are long or short 100 contracts of corn or 300 contracts of the S&P 500 futures, the CFTC classifies you as a big speculator. Brokers send reports on positions that reach reporting levels to the CFTC. It compiles them and releases summaries once every two weeks.

The CFTC also sets up the maximum number of contracts, called position limits, that a speculator is allowed to hold in any given market. At this time, a speculator may not be net long or short more than 2400 contracts of corn or 500 contracts of the S&P 500 futures. These limits are set to prevent very large speculators from accumulating positions that are big enough to bully the markets.

The CFTC divides all market participants into three groups: commercials, small speculators, and large speculators. Commercials, also known as hedgers, are firms or individuals who deal in actual commodities in the normal course of business. In theory, they trade futures to hedge business risks. For example, a bank trades interest rate futures to hedge its loan portfolio, or a food processing company trades wheat futures to offset the risks of buying grain. Hedgers post smaller margins and are exempt from speculative position limits.

Large speculators are those traders whose positions reach reporting levels. The CFTC reports buying and selling by commercials and large speculators. To find the positions of small traders, you need to subtract the holdings of the first two groups from the open interest.

The divisions between hedgers, big speculators, and small speculators are somewhat artificial. Smart small traders grow into big traders, dumb big traders become small traders, and many hedgers speculate. Some market participants play games that distort the CFTC reports. For example, an acquaintance who owns a brokerage firm sometimes registers his wealthy speculator clients as hedgers, claiming they trade stock index and bond futures to hedge their stock and bond positions.

The commercials can legally speculate in the futures markets using inside information. Some of them are big enough to play futures markets against cash markets. For example, an oil firm may buy crude oil futures, divert several tankers, and hold them offshore in order to tighten supplies and push futures prices up. They can take profits on long positions, go short, and deliver several tankers at once to refiners in order to push crude futures down and cover shorts. This manipulation is illegal, and most firms hotly deny that it takes place.

As a group, the commercials have the best track record in the futures markets. They have inside information and are well-capitalized. It pays to follow them because they are successful in the long run. The few exceptions, such as orange juice hedgers, only confirm this rule.

Big speculators used to be highly successful as a group until a decade or so ago. They used to be wealthy individuals who took careful risks with their own money. Today's big traders are commodity funds. These trend-following behemoths do poorly as a group. The masses of small traders are the proverbial "wrong-way Corrigans" of the markets.

It is not enough to know whether a certain group is short or long. Commercials are often short futures because many of them own physical commodities. Small traders are usually long, reflecting their perennial optimism. To draw valid conclusions from the CFTC reports, you need to compare current positions to their historical norms.

The modern approach to analyzing commitments of traders has been developed by Curtis Arnold and popularized by Stephen Briese, publisher of the Bullish Review newsletter. These analysts measure deviations of current commitments from their historical norms. Bullish Review uses the following formula:

Current Net - Minimum Net

COT Index =

Maximum Net - Minimum Net

where COT Index = commitments of Traders Index.

Current Net = the difference between commercial and speculative net positions.

Minimum Net = the smallest difference between commercial and speculative net positions.

Maximum Net= the largest difference between commercial and speculative net positions.

Net Position = long contracts minus short contracts of any given group.

When the COT Index rises above 90 percent, it shows that commercials are uncommonly bullish and gives a buy signal. When the COT Index falls below 10 percent, it shows that commercials are uncommonly bearish and gives a sell signal.

Insider Trading

Officers and investors who hold more than 5 percent of the shares in publicly traded companies must report their buying and selling to the Securities and Exchange Commission. The SEC tabulates insider buying and selling and releases this data to the public once a month.

Corporate insiders have a record of buying stocks cheap and selling dear. Insider buying emerges after severe market drops, and insider selling accelerates when the market rallies and becomes overpriced.

Buying or selling by a single insider matters little. For example, an executive may sell shares in his firm to meet major personal expenses or may buy shares to exercise stock options. Analysts who researched legal insider trading found that insider buying or selling was meaningful only if more than three executives or large stockholders bought or sold within a month. These actions reveal that something very positive or negative is about to happen to the firm. A stock is likely to rise if three insiders buy in one month and to fall if three insiders sell within a month.

Stock Exchange Members

Membership in a stock exchange - particularly as a specialist - is a license to mint money. An element of risk does not deter generations of traders from paying hundreds of thousands of dollars for the privilege of planting their feet on a few square inches of a crowded floor.

The Member Short Sale Ratio (MSSR) is the ratio of shorting by members to total shorting. The Specialist Short Sale Ratio (SSSR) is the ratio of shorting by specialists to shorting by members. These indicators used to serve as the best tools of stock market technicians. High readings of MSSR (over 85 percent) and SSSR (over 60 percent) showed that savvy traders were selling short to the public and identified stock market tops. Low readings of MSSR (below 75 percent) and SSSR (below 40 percent) showed that members were buying from the bearish public and identified stock market bottoms. These indicators became erratic in the 1980s. They were done in by the options markets, which gave exchange members more opportunities for arbitrage. Now it is impossible to tell when their shorting is due to bearish-ness or to arbitrage plays.

Odd-Lot Activity

Odd-lotters are people who trade less than 100 shares of stock at a time - the small fry of the stock exchange. They remind us of a more bucolic time on Wall Street. Odd-lotters transacted one quarter of the exchange volume a century ago, and 1 percent as recently as two decades ago. Odd-lotters as a group are value investors. They buy when stocks are cheap and sell when prices rise.

The indicators for tracking the behavior of odd-lotters were developed in the 1930s. The Odd-Lot Sales Ratio measured the ratio of odd-lot sales to purchases. When it fell, it showed that odd-lotters were buying and the stock market was near the bottom. When it rose, it indicated that odd-lotters were selling and the stock market was near the top.

The Odd-Lot Short Sale Ratio was a very different indicator. It tracked the behavior of short-sellers among odd-lotters, many of whom were gamblers. Very low levels of odd-lot short sales indicated that the market was near the top, and high levels of odd-lot short sales showed that the stock market was at a bottom.

These indicators lost value as the financial scene changed in the 1970s and 1980s. The intelligent small investors moved their money into well-run mutual funds, and gamblers discovered that they could get more bang for their money in options. Now the New York Stock Exchange has a preferential mechanism for filling odd-lot orders, and many professionals trade in 99-share lots.

|